By Timothy O’Neill

In printed circuit board (PCB) assembly, solder mask integrity is paramount. This protective layer, designed to shield the copper surfaces and prevent solder bridging between components, plays a crucial role in ensuring the reliability and functionality of electronic devices.

However, solder masks can face several issues such as crazing, delamination, peeling, and the presence of waxy or oily residues. These defects can lead to complications like micro solder balling, bridging, and solder snail trails, especially noticeable after wave soldering processes.

Not only do these challenges compromise the PCB’s quality and long-term reliability, but they can also lead to significant production rework and increased costs.

Common Causes of Solder Mask Problems

Solder mask issues can arise from several factors, ranging from the manufacturing process to the materials used. Here are some common causes:

- Inadequate Surface Preparation: For a solder mask to adhere properly, the PCB surface must be clean and free of contaminants. Any residue or oxidation/moisture can significantly affect the mask’s adhesion.

- Incorrect Curing: Solder masks require proper curing to achieve optimal adhesion and durability. Under-cured solder masks are susceptible to any liquids and can be easily damaged during the soldering process due to flux absorption and improper volatilization. Insufficient hardener in the solder mask’s make-up can also cause it to never fully harden after curing.

- Solder Mask Porosity: Solder masks can sometimes exhibit porosity depending on the type of solder mask used, the application process, and the curing process. Chemicals such as flux and cleaning agents as well as moisture could seep through these tiny holes. This can lead to reliability issues as well as corrosion or other damage over time.

- Environmental Factors: The solder mask can absorb chemicals during PCB manufacturing, which may become highly hygroscopic or corrosive. When exposed to field conditions, these absorbed substances can cause the PCB to experience failures due to the combined effects of humidity, heat, and electrical stress.

Nearly all instances of solder mask delamination are related to the PCB itself, rather than to the flux or equipment used in the assembly process. If the solder mask shows visible damage or if there are oily or waxy residues present, this could indicate issues with adhesion or improper curing of the mask, or potentially a combination of both factors.

Other signs of a problem include solder snail trails, micro solder balling, or bridging following the soldering process. It is crucial to identify and address these issues to prevent compromised PCB performance and integrity.

Here are a few simple tests the engineer can do on the shop floor to help zero in on the root cause.

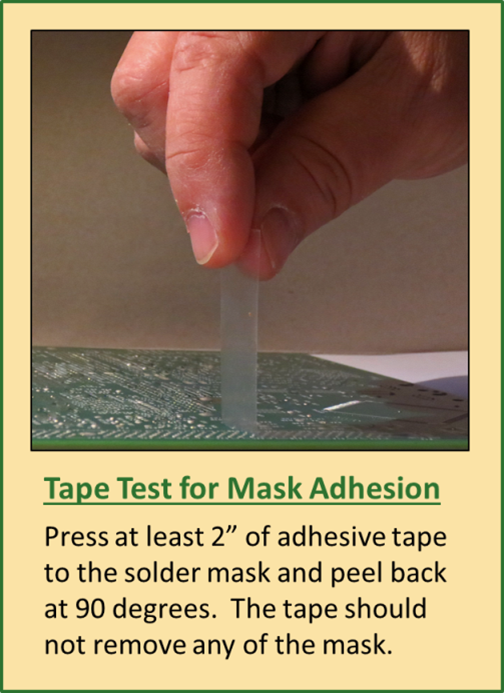

Adhesion Check: The Tape Test

This test involves applying a piece of transparent adhesive tape of at least 2 inches in length. Press the tape on the board and pull it up quickly at an angle approximately 90 degrees to the PCB surface (Figure 1). If the tape pulls the mask off, you are looking at an adhesion problem. The official IPC test method (2-4-28) calls out 3M Brand 600 ½ inch (aka “Scotch”) tape, but if that’s not what’s in your dispenser, use whatever is there.

If the mask lifts, observe the condition of the copper underneath. If the copper is shiny, it was likely not properly prepared for solder mask application. A matte finish indicates proper cleaning and roughing of the surfaces before mask application.

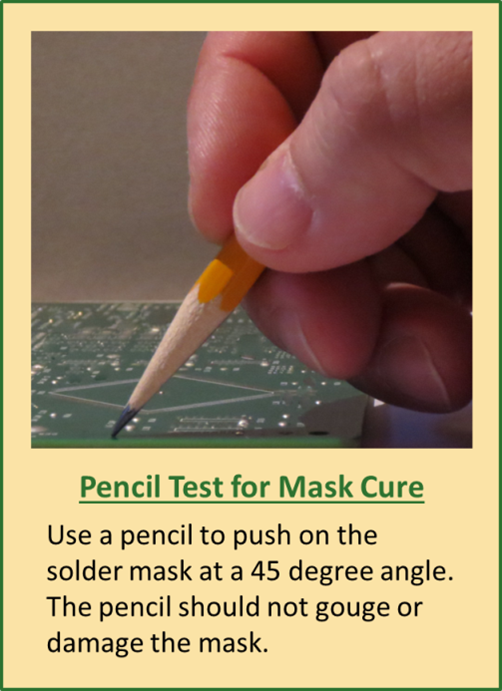

Cure and Hardness Checks

You can try the following three tests to check the curing and hardness of the mask.

The Pencil Test: Locate a wooden pencil and give it a fresh sharpening. Hold it at a 45° angle and press firmly away from you (Figure 2). If the solder mask lifts or gouges, it is not sufficiently hard. This may be the result of improper curing or insufficient hardener added to the mask before curing.

The pencil you used was likely a #2H (we’re all familiar with those from standardized tests). Pencils are graded on a hardness scale, and any graphite graded less than #6H should not gouge solder mask. If you want a #6H, or a complete kit of varying hardness pencils, they are sold at art supply stores.

The Bake Test: Conduct this test by placing the PCB in an oven preheated to 175°C and allow the board temperature to reach 155°C. Once at this temperature, maintain the board at 155°C for exactly 60 minutes. Ensure that the oven has adequate ventilation to remove any harmful fumes and plasticizers, preventing them from redepositing onto the solderable finishes, which could result in dewetting or poor wetting issues.

If issues such as crazing, delamination, and the presence of oily or waxy residues are resolved after this treatment, it indicates that the solder mask was under-cured, and the additional baking has helped complete the curing process.

However, if the problems persist, this may suggest that the solder mask’s formulation was incorrect, potentially due to an insufficient amount of hardener being added during preparation.

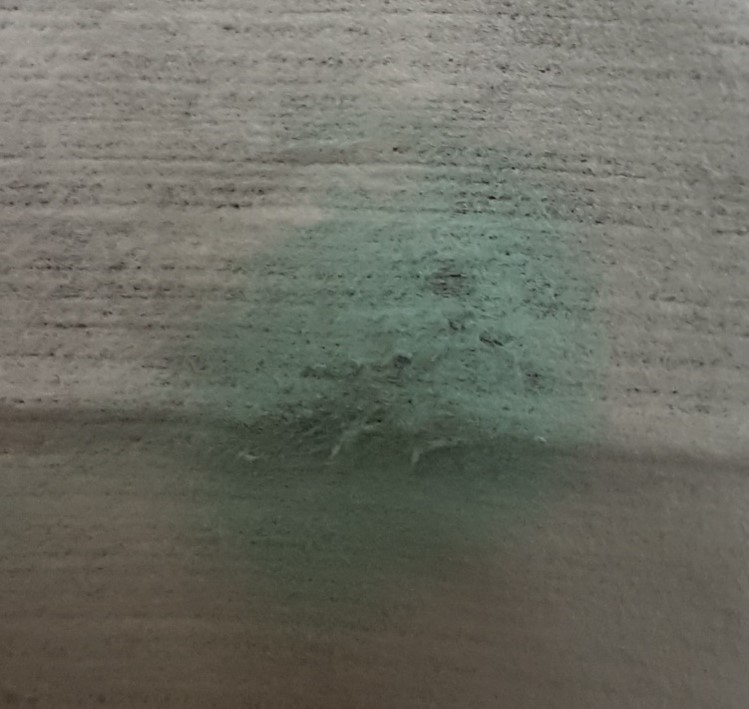

Solder Mask Check Wipes: BLT Circuit Services offers easy-to-use Solder Mask Check Wipes. These wipes are designed for a quick qualitative test to identify under-cured solder mask on PCBs. To use, remove a wipe from the package, ensuring the package is re-sealed. Rub the wipe on the PCB with moderate pressure for about 10-15 seconds in various areas.

If the solder mask is under-cured, color from the resist will transfer onto the wipe, indicating issues with the mask’s adhesion or curing (Figure 3.). If such a transfer occurs, it suggests the PCB may have defects and should be reported to the supplier for correction.

Case Study: How Flux Chemistry Can Exacerbate Solder Mask Issues

While solder mask problems typically stem from application issues which can be identified by the checks previously described, interaction between the mask and the flux chemistry can also cause problems in rare occasions. Here we describe a situation in which the problem was at least partially flux related.

The Problem

In this case, a liquid flux seemed to be interacting with the solder mask, making it appear hazy and crazed, even lifting it from substrate. The issue appeared to happen most frequently and severely around traces. A review of the wave solder process indicated no unusual steps, parameters, or exposure times that could cause solder mask damage, and the PCB fabricator insisted it was a flux problem.

Troubleshooting and Solder Mask Tests

We asked the user to perform a few of the simple solder mask tests while we researched the flux lot number to see if there were any production changes or other customer concerns associated with it. We found no changes or concerns on record, but this particular flux was a highly specialized, small-batch material. We hypothesized that perhaps some variations could have taken place within its shelf life, so we tested a sample sent back from the user, but again found no issues.

Meanwhile, the mask failed both the tape test and the solder mask wipe test. Then, in our further investigation of the mask and flux chemistries, we discovered that the mask was a newer, halogen-free product.

Identifying the Cause

The mask’s unique composition and lack of sufficient curing caused it to remain highly porous. As a result, the flux was absorbed into the subsurface of the solder resist, where it could not properly volatilize as expected during the preheating phase.

Once the board encountered the solder wave, the absorbed flux boiled between the resist and copper layers, undermining the adhesion between the solder resist and the base copper tracks. This information together with the solder mask test failures helped the assembler demonstrate the problem to their PCB fabricator and drive a resolution.

Final Thoughts

It’s not unusual for the solder chemistry vendor to drive the root cause analysis of soldering issues. In fact, it makes perfect sense. The soldering technical support staff sees so many varied and different processes and problems, they are natural troubleshooters and a great resource for process engineers. Proper evaluation of material performance often relies on tests borne from the cause-and-effect knowledge that is only gained through experience.

A quality vendor should not attempt to pass the responsibility for process issues down the line but rather commit to leading the customer to the fastest, most effective solution, regardless of fault. The “pass the buck” strategy can backfire and jeopardize business; yet, for some inexplicable reason, it is still commonly deployed. Until it’s eradicated, keep calling the soldering guys; much of our valued experience is acquired through our customers’ challenges.